According to the Bruce Mclaren website Ford entered eight cars at Le Mans in 1966, three by Shelby American, three by Holman-Moody and two by the British Alan Mann team. These entries followed a Ford decree laid down after the 1965 fiasco that no team, no matter how good, could be expected to take care of more than three cars. Carroll Shelby’s star driving team could have almost been called the All Blacks. The Shelby team was comprised of Dan Gurney with Jerry Grant. Ken Miles (Christian Bale in the movie) who was paired with New Zealander Denny Hulme. Two more Kiwis, Bruce McLaren and Chris Amon, drove Shelby’s third entry.

The irony of GT 40 production comes when you look backwards to 1913, which is when Henry Ford was installing his first moving assembly line for mass production. This was a pivotal moment for all of us because whilst he didn’t know it at the time, he had just played a key role in laying the groundwork for consumerism, which would begin in earnest at the end of World War II. Wartime production had significantly benefited American companies and the production requirements for war had extracted the USA from depression. The efficiencies of factories geared for war production and the latest mass production technology along with the improved finances of Americans meant there was money left over to buy stuff…which America was now really good at making. Televisions, motor cars, appliances and more and more and more. The good times rolled.

Along the way the gilded edges of the good times have worn off and many production centric enterprises are struggling with how to stimulate demand. In the 1960’s, the Mad Men on Madison Avenue certainly helped. They were the gods of demand creation and they were super smart, they still are. These days, the best advertising companies are still punching hard, but the gilded edges have worn off for many. This is why rapidly growing markets like China hold such strong appeal to industries with mass production addictions. It enables an enterprise with a production mindset to rationalise its strategy and existence. What’s getting harder and harder for such companies is the ability to see the rapidly evolving behaviour of their once loyal consumers. These days, many have bigger concerns to deal with. Mindless materialism is on the way out, so what’s next?

As an individual not being able to see where you are going is dangerous. As an organisation, not being able to see is also dangerous, so much so, that the affliction even has its own name. It is called marketing myopia. The concept, originally proposed by Theodore Levitt in the early 1960’s demonstrates the connection between failing to market successfully and organisational failure. Levitt (1960) believed that organisations diagnosed with marketing myopia were more focused on selling products than creating customer satisfactions. The result of such a misguided focus he believed was an organisation primed and positioned for significant decline, fiscal failure, or extinction. Levitt was not alone in his thinking. Maciariello (2008), co-author of The Daily Drucker reported, “Peter F. Drucker is well known for stating that there is only one valid purpose for a business: to create a customer. And there are only two basic business functions: marketing and innovation.” Drucker’s thinking is important contextually too, because he was Levitt’s friend and sometimes editor.

Levitt developed four preconditions for diagnosing marketing myopia and each precondition demonstrated that enterprises leveraging business models focused on selling the bulk of their production into so-called ‘endless’ growth markets were highly vulnerable to the effects of marketing myopia. Growing up on both sides of World War II, Levitt witnessed the birth of mass production and consumerism. He was quick to see the issues with mass production dynamics and he quickly recognised that in failing organisations production mindsets overshadowed the more critical mindset of producing what he called ‘customer satisfactions’. New Zealand examples of enterprises displaying mass production mindsets include enterprises involved in selling undifferentiated commodity products like timber logs, tourism, dairy powder, bulk wine, and red meat. Many of the companies involved in the output of these products and services have taken big bets on continued explosive growth in markets like China. This addiction according to Levitt (1960) placed such enterprises at risk. The need to feed their production habit meant they were more likely to focus on ‘selling products’ instead of focusing on producing ‘customer satisfactions’.

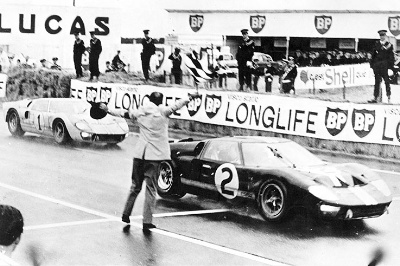

The evidence submitted by Levitt (1960) clearly highlighted that history did not play well for enterprises with production mindsets, especially if they were handicapped with a cult belief in growth markets like China. China has consumers too, and consumers want and need, and not surprisingly, demand… customer satisfactions. In these situations, enterprises trading commodities rarely achieve a premium and price is nearly always the clearance mechanism for the production output. It is time to argue for the investment into and development of better marketing approaches capable of mitigating marketing myopia and enhancing the successful pursuit of premium for New Zealand enterprises. It’s time for New Zealand to pursue premiums like the famous GT 40 drivers pursued victory at Le Mans.

Ends.